Paul Goldberger on Dumbo, ‘A Metaphor For the Rediscovery Of the American Downtown’

By: Zoe Rosenberg

In the 1970s, when the then-fledgling developer David Walentas noticed artists fleeing SoHo, he asked where they were going. The answer, from a chance encounter in an elevator, would change his life and rewrite an entire neighborhood: Dumbo.

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

Today, the picturesque Brooklyn waterfront enclave is known for its ritzy real estate, cultural attractions, and Instagram-famous vistas. It’s also synonymous with Walentas, who, along with his wife, Jane, and son, Jed, has spent the past four decades coaxing Dumbo into a place to “Live, Work & Play,” per Jane’s early motto for the neighborhood.

In the late 1970s, when Walentas first crossed the Brooklyn Bridge into the former hub of industry, Dumbo—named by residents in 1978 after an acronym for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass—was desolate, save for a few remaining businesses that had resisted the area’s deindustrialization, as well as the artists who moved into those high-ceilinged former workspaces.

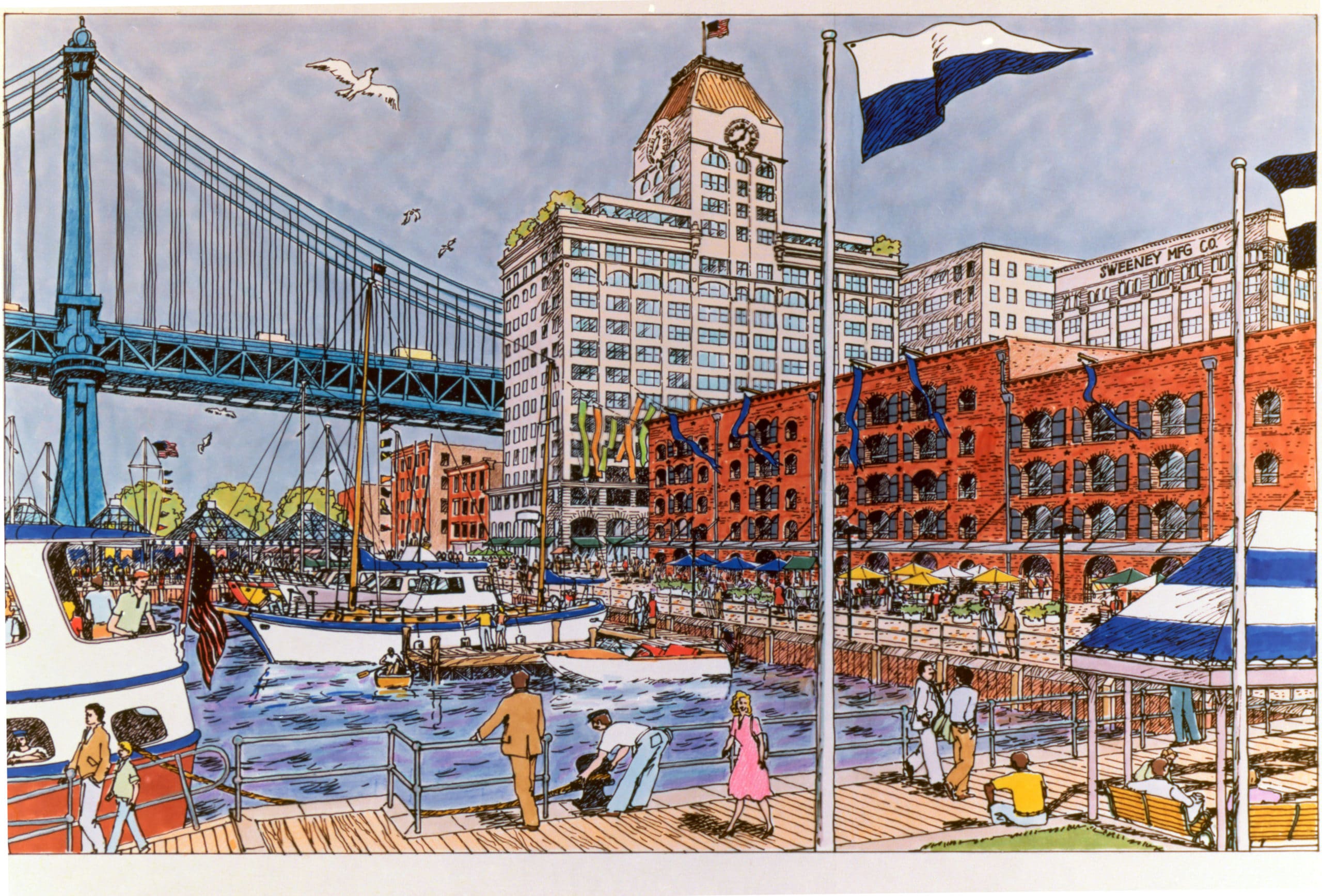

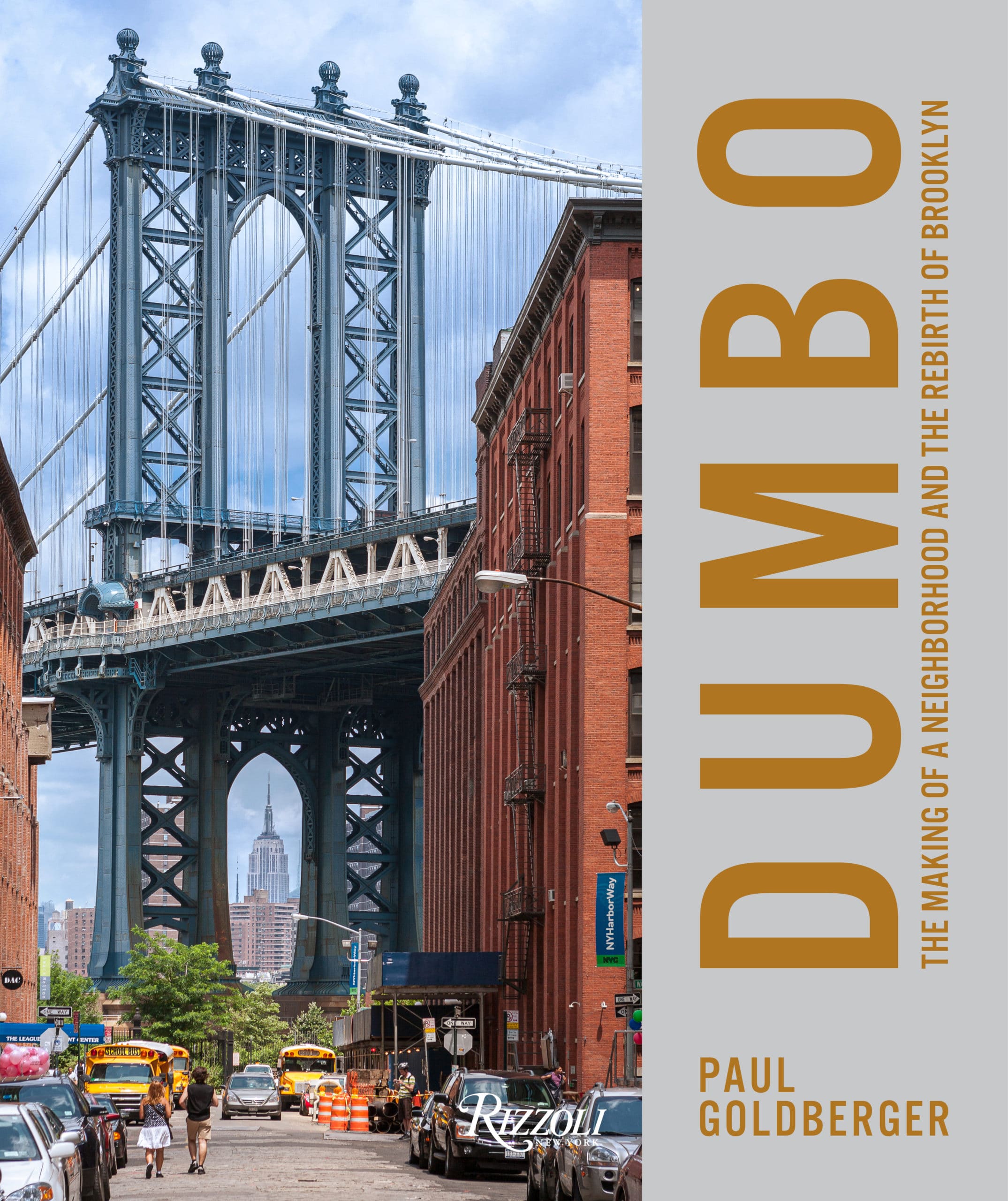

In the new book from Rizzoli, DUMBO: The Making of a Neighborhood and the Rebirth of Brooklyn, the architecture critic Paul Goldberger outlines the enclave’s reinvention—from 1700s village to industrial waterfront to one of Brooklyn’s priciest residential neighborhoods—alongside an array of archival and modern drawings and photographs. He credits Walentas’s intuition, vision, and patience for creating a neighborhood that, today, is a chorus of small businesses, cultural attractions, and dazzling residential real estate.

Why did you want to work on this book?

I’ve always loved Dumbo. I’ve never lived there, but I’ve always thought it was a wonderful place. I love the combination of dense industrial urbanity and the beautiful waterfront and the bridges. I love the idea of this place that, in some ways, seems so intensely New York, and yet it’s different from any other place in New York.

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

The other thing about it is that it’s just such an interesting story. One guy sort of discovers it and turns it into a neighborhood over a whole generation—the story of David Walentas getting it and imagining what it could be and then having the patience to see it through. It became a life’s work for him. It almost fell apart so many times, and he just kept struggling with it. Real estate isn’t always full of interesting stories. This one is.

You write that “Dumbo is a metaphor for the rediscovery of the American downtown.” What did you mean?

What I meant by that remark is that you see in this place—which is really only a few blocks—the whole arc of American cities: starting out as a little village, then industrialization of the waterfront, then abandonment and difficulty and struggle, and then renewal where people live with a recreational waterfront.

You draw a lot of comparisons between SoHo and Dumbo. Although both neighborhoods have experienced gentrification—making them less livable for the artists who once occupied them—Dumbo was able to retain its artistic community much longer than SoHo. Why do you think that’s the case?

Here we come back to David Walentas and the fact that he was not only more patient than most real estate developers; he was smarter than most real estate developers. He knew how important arts and culture were to creating neighborhoods.

He did a couple of things. First, he seeded the neighborhood by giving arts organizations, galleries, theatre companies, and so forth space—for free or very cheap. While it’s true that Dumbo was started by artists who came as squatters living illegally in lofts the way they did in SoHo, instead of trying to throw them out at the beginning, Walentas actually tried to bring in more.

And then they gave long-term leases to certain nonprofit galleries and other organizations to ensure they wouldn’t be priced out. Walentas wanted Dumbo to be successful, but he did not want Dumbo to precisely follow the model of SoHo. It’s interesting that Dumbo does not have a huge amount of destination shopping, for example. It’s not like SoHo where you have block after block of boutiques, and the whole thing sometimes feels like a mall without a roof. Dumbo has a lot of retail that is still local—retail that serves people who live there.

In the mid-2000s, the Landmarks Preservation Commission started the process of creating a Landmark District in Dumbo, and the Walentases backed it then. That’s an unusual strategy for a developer. Can you explain why they did that?

The Walentases’s interest was always in preserving the neighborhood and having it evolve, but in a very careful, managed way that would keep the older buildings as the heart of Dumbo. Designating it as a Historic District doesn’t mean absolutely nothing can ever change; it means nothing can change without the permission of the Landmarks Commission.

They have continued—not just the Walentases, but others as well—to construct new buildings in Dumbo, but they didn’t want to see it change dramatically. Walentas originally bought Dumbo because he loved the old buildings that were there. Most of his career, he has been renovating older buildings. He had no particular interest in building new. He felt the Historic District designation would prevent somebody else from coming in someday and doing something really stupid, like tearing down half of Dumbo and turning it into, you know, Long Island City.

So, essentially Landmarks looked at what David had already achieved and said, “This is something we want to preserve.”

Precisely. Those buildings really do constitute an ensemble; it has real quality, and it’s worth preserving. It’s definitely been a positive thing, and Walentas was smart enough to know that. He also knew what only some developers know, which is that the Landmarks process is not always your enemy.

Dumbo has gone through many different waves of gentrification. When would you say the most recent one began, and what does it look like?

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

There have been at least two distinct waves of gentrification in the Walentas era, if you want to call it that. So, the first phase was commercial gentrification, when Dumbo was just a business neighborhood, because the zoning did not permit residential use. And while there were a bunch of illegal loft-dwellers, Walentas just inherited them. He didn’t create that. And it took a long time—between 15 and 20 years—to actually evolve it into a residential neighborhood as industry was fading. Finally, the City Planning Commission agreed to switch the zoning in Dumbo to allow residential use.

And then the second phase has been residential gentrification. First, they converted One Main Street into apartments, and that sold out before it was finished. So, it was clear that there was a huge demand. And they just kept going, turning multiple other buildings into apartments. Generally, they sold everything as fast as they could convert it. Both Walentas and other developers have also built a few new residential buildings as well.

You could say now that Dumbo has become so desirable that we’re in a third phase: a mature and expensive neighborhood.

In the book’s closing thoughts, you write that authenticity doesn’t come naturally to cities today—that if authenticity is going to exist, it needs to be managed or nurtured over time. That feels like a nod to what the Walentases did, but can you expand on what that means more broadly?

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

Photo Credit: Rizzoli USA

What David, Jed, and Jane understood was that if you gave up some income and rented to nonprofit and arts organizations, you could strengthen the neighborhood in the long run. To be fair, in the very early years, it’s not like they were going to get high-rent-paying tenants, anyway. People were not banging down the door to rent space for a lot of money in Dumbo. So Walentas was strategic; he knew what he could and what he couldn’t do.

They also understood that every great neighborhood—every great city—is a mix of design, intention, and accident. If they planned everything to the last square inch, it was not going to work. They had to be a little loose about it and just let a few things happen. In a real neighborhood, there’s never perfection. There’s always a little bit of mess. This is not Disneyland, after all. It’s still a real New York neighborhood. If you try to micromanage every last inch, you also get rid of a certain degree of authenticity.

Is there a next Dumbo in New York?

There’s nothing like this amazing combination of waterfront, great architecture, awesome infrastructure, and two of the greatest bridges in the world coming together. The combination of raw materials, so to speak, and a developer with Walentas’s sensitivity might just be a once-in-a-lifetime combination.

Interview has been lightly edited and condensed.